We want a lot of things from our government: improving living standards, security, honesty, and rhetorical validation. We want the feeling of being part of something greater than ourselves, and of being different from everyone else. Because we want these things to differing degrees—and in differing ways—we need to have a system which synthesizes an overwhelming number of often incompatible demands into a final decision that feels fair, even to those who lose out.

Democracy has been far more successful at this than any form of oligarchy or monarchy. Successful 21st-century democracies collate and adjudicate the population’s preferences via representation (cf. direct democracy and demarchy). In such a system, candidates tell voters what they will do, and citizens exercise influence by choosing which will govern.

When there are only two options, voters do not have very much power. They do not get to express themselves except by a directional preference along one axis, and the axis is determined by the bilateral maneuvering of just two agents (i.e., the two parties). Most countries have different election laws which allow multiple parties to be represented in the legislature (“Proportional Representation”). This is a much better system, and we should modify our laws to allow for this.

Against Excluding “Bad” Parties

A common belief is that any perspective which cannot command a plurality of the vote is too extreme to be represented in the legislature—this is usually expressed in terms of keeping “Nazis” out of power. This is a conceptual error. Excluding minor parties from the legislature does not eliminate those beliefs from the electorate but rather encourages those who hold those beliefs to integrate themselves into the larger parties.

The mainstream parties are amenable to integrating smaller tendencies because many two-party elections are determined by margins smaller than even minor parties. A center-right party whose normal constituency is 42% of the population can decisively defeat a 45% center-left party if a 5% hard-right section of the electorate can be convinced to hold their nose and support them as the “lesser of two evils.” This is not a far-fetched scenario: in the 2000 Florida presidential election, the left-wing Green Party got 1.64% of the vote to the center-left Democrats’ 48.838%. Despite being 1/30th the size, the Greens’ vote was 100x the margin needed for the Democrats to overcome the Republicans’ 48.847%. Had they been more successful in integrating the Green tendency into their pre-election coalition, they would have won the state and thus the 2000 election.1

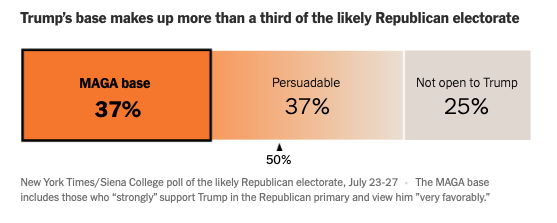

Because integration in a two-party system happens informally, opaquely, and prior to voting, it can lead to both under-representation and over-representation. Under-representation of an extremist minority is easy to understand. While 6% of voters view socialism “very positively”, less than 6% of districts are both Democratic-leaning and have socialists as the plurality of Democratic-aligned voters, so they get underrepresented in the national body (~1% of our current Congress has been part of a socialist organization while in office). The gap between left-wing voters and their number of representatives is filled by a mild over-representation of non-socialist (some combination of progressive, centrist, and conservative) Democrats. Yet pre-election integration can also lead to the amplification of a party’s more extreme wing. In the contemporary United States, about ~45% of the electorate is Republican or Republican-leaning, and ~37% of that is the MAGA base. This is ~17% (.45*.37) of the active electorate, yet because MAGA is the plurality of Republican-aligned voters (outnumbering actively anti-MAGA Republican voters 2-1), almost all elected Republicans espouse MAGA. (I suspect many are insincere, and I also suspect that many have become more sincere with time.) What would in Germany be a significant minority party (equivalent to the AfD, which just won 20% of the vote) can instead, by dint of being the plurality of a plurality, control the government. The worst case scenario—an extremist minority gaining power—is in this case made possible by the system being closed off.

In contrast, legislative coalitions happen more formally, transparently, and after the election. I do not want to seem pollyannaish on this point: legislatures have plenty of shady deals. But because coalition agreements are made between formally different groups whose relative heft is clear, parties must be ready to explain any deviations from their base’s ideal in terms of what they got in exchange. The most palatable (low-cost) parts of each’s priorities relative to the perceived upside (high-benefit) are exchanged, and so a net win-win deal is struck. In the aggregate, across many election cycles, most voters will be fairly well served from the accumulation of many such minor win-win compromises.

(If you do want more information on the Nazi example, I wrote a separate piece on it here)

Competition Disciplines Parties

Beyond representing sincere beliefs of voters in an electorate to the rough degree to which they are held (which is very good), competition from smaller parties discipline the major parties to better represent voters in a way analogous to how businesses are disciplined from competition from other businesses.

When misdeeds come to light, voters should be able to punish them without being forced to vote for a party actively opposed to their values. Political leaders are prone to anti-social behavior just like anyone else, and, due to excluding the meek, likely disproportionately so. Even relatively advanced democracies will have corruption: the Irish Taoiseach Charles Haughey illicitly accumulated a vast fortune across decades and Lyndon Johnson made millions from investments made in his wife’s name.2 When the head of Norway’s Rødt Party (devoted to creating "what Karl Marx called communism") stole a pair of Hugo Boss sunglasses from a store in the Oslo airport, he was promptly replaced despite having doubled his party’s vote share in two consecutive elections. If Norway were a two-party system, Rødt voters might be reluctant to defect to the “everybody who hates Rødt” Party; this reluctance, being obvious to leadership, would in turn weaken the pressure on that leadership to risk cleaning house. Norway’s strong multi-party system, however, gives left-wing voters viable alternatives in the Socialist Left Party and the Labour Party. While neither is communist, the leadership of Rødt realized that keeping an unpopular leader was a bigger risk than getting rid of him. Now Norwegian left-wing voters have three non-corrupt choices presenting different visions of the future, rather than the one corrupt one which we might expect in a two-party system.

It’s not just illegal activity which two polarized parties insulates leadership from addressing. For the past two decades, the US’s center-left party has become increasingly gerontocratic. Their electorate skews much younger than their opponent’s, but its leadership has continued to front frail, senile, and dying boomers. When the party does promote rather than scorn younger candidates, the criteria seems to be that they be unpopular with actual young people. While gerontocracy is perfectly rational from the perspective of any given ancient party leader, it is not socially desirable. In a multi-party system, Democrats’ behavior would have seen them bleeding young voters to another party for nearly 15 years now, presenting them a choice: would they rather adopt a less contemptuous posture, or see their base shrink? Either option, in my mind, is totally acceptable—not every party is for everyone, and old and young people might genuinely differ enough on issues of culture, economics, and climate that they are better served having their interests bargained separately. The SPD in Germany represents about twice as many retired unionists as active ones, and the Australian Labor Party has ceded about half their young electorate to the Greens. But young people in America have nowhere to go, and so the Democratic leadership are stuck with a major constituency they frankly wish they did not have to represent.

Probably the most egregious example of this was the party’s arrogant insistence on keeping Joe Biden in the race. Despite ending the 28-year boomer president streak by being even older than the boomers, the party asserted that Biden was fine well past the point of credulity.3 It had not mattered that most Democratic voters did not want him to run again, as they were powerless to punish the party (unless they were willing to tolerate another Trump win—and if they were they wouldn’t be Democrats in the first place). When, however, polling showed Trump sweeping 80% of the electoral college (likely annihilating the rest of the party in his coattails), the Democrats found the wherewithal to push Biden out. A more credible defection threat to a competing anti-Trump party would have almost certainly caused a sooner and more successful pivot, but that would have required voters having alternatives not totally at odds with their values.

There are people who think that voters are too clueless to know whether parties do what they say they do. While voters often cannot name specifics about important government actions, they do not need to because voters exist in social networks. Your union, your newspaper, your church, your friends, and your employer all have an interest in keeping you relatively informed. They might not be 100% accurate, but they are disincentivized from being consistently or flagrantly dishonesty. Different institutions have different issues which they are motivated to present in a skewed way, and it is the parallax of these differences which voters passively synthesize. These synthesizes do not have to be especially accurate individually as long as they are on average fine and correlated with reality (and they are because they both are told about the world and notice confirming details). If some workers over-rely on their union, others on their boss, others on local non-profits, and others on their own lying eyes, then these vaguely cancel out in a way which makes governing well a pretty good way to win votes.

An analogy with consumer prices is useful: I know that Safeway is more expensive than Winco. How is that possible when there are tens of thousands of products offered by each and I am not confident that I know the prices of even the things I buy weekly within ±30%? Because of what I am told and what I notice. Everyone tells me Winco is cheaper than Safeway, and I notice that when I shop there I spend less money than I do at Safeway despite buying more things. This is a powerful combination, and it is why Winco actually does sacrifice revenue to make their prices cheaper than Safeway. Winco only has profit margins of ~2%. If it decided to raise its prices by 30%, it could generate a larger profit even if a majority of customers chose to shop elsewhere.4 They don’t because they know that their customers—on average not carefully attuned to any given item’s price—would indeed stop shopping with such a large price increase. How would they know what Winco did? They would be told about the overall price raise: their most money-conscious friend, who is among the small fraction of shoppers accurately tracks prices, would complain about the changes; the local news would probably do a segment on the dramatic about-face; Safeway and other stores would put out ads comparing their prices on select goods to Winco’s. And as this barrage of anti-Winco publicity comes in, the consumer would pay attention to their bill and notice that it is indeed consistently higher week after week. None of this actually needs to happen to keep Winco from usually not raising its prices, because we know what would happen if they did. We should trust that voters similarly can collectively understand politics enough to incentivize good decisions, even if individual voters appear ill-informed and incoherent on the details of policy.

Consider the example of Britain’s Liberal Democrats (“LibDems”): they came into government in 2010 on a pledge to eliminate university tuition fees and fight Conservative austerity. They then promptly voted to triple fees and help the Conservatives implement austerity. In the next election, they lost 65% of their vote and 85% of their seats. How did voters know to abandon them? They were told by others (classmates, coworkers, newspapers, protestors, the Labour Party), and they noticed the increased fees and stagnant wages.

Parties Are Not Mere Inversions of Each Other

In order to rise above the cacophony, people with compatible interests band together in (or are banded together by) political parties. I want to have more money is a thought shared by many, and they might join with co-workers in a Labor Party (which promises to raise wages), co-consumers in a Liberal Party (which promises to lower prices), or co-ethnics in a National Party (which promises to increase opportunities for people like them). People, having multiple interests and multiple ways to fulfill those interests, choose a party from some mix of perceived sincerity, plausibility, magnitude, and vibes of the promised policies. Despite the fact that they are competitors, parties are not mere inversions of each other, and thus formal cross-party compromise opens up room for net positive sum results.

It should be obvious that a parties with overlapping values, like a social liberal Progressive Party5 and a Green Party, could find policies which please both of them at once: take whatever economic objective our fictional Progressive Party wants to achieve (science R&D, counter-cyclical stabilization, and redistribution of market income) and channel that through Green measures: clean energy R&D, Keynesian Green Jobs, and carbon taxes. Maybe these are not quite the perfect way to achieve each of these goals individually, but there is enough synergy it is possible to have each spent dollar do double duty. Plus the Greens likely somewhat value the Progressives’ economic policies, and the Progressives likely somewhat value the Greens’ ecological goals.

Hypothetical: Our Progressive Party wants to raise wages by raising productivity, and they find that $100 billion in broad-based science funding will increase wages 10% over a decade. The Greens want to cut down on CO2 emissions, and find that $100 billion in solar panels donated to the third world would decrease global emissions by 10 billion tons. Individually, both parties find this the most efficient way to achieve their respective goals. However, if they find that $100 billion in clean energy R&D will generate 8% wage growth and prevent 8 billion in emissions, then in coalition both parties can achieve most of their objectives at once at half the cost of doing both. If money is not overly restrained, they can either add on $20 billion of each of the other programs to bump up the full 10%/10b tons benefits, or make the investment in clean energy R&D $125 billion for 10%/10b tons, a pareto optimal alternative in our scenario.6

Parties with different values often come to the same policy positions. Many conservative parties worldwide support old age pensions because they find the elevation of the dignity of elder’s socially desirable, at the same time social democratic parties support those same pensions as part of an egalitarian commitment to fighting poverty. Both libertarians and socialists in America generally support the legalization of cannabis. That said, issues that are widely agreed upon are not “political”, so we should not assume this will resolve much.

Even parties fundamentally opposed to each other can come out with mutually beneficial (non-zero-sum) compromises. Libertarians are united by an opposition to state bureaucracy, and their policies tend to create inequality. Socialists are united by opposition to inequality and their policies tend to create state bureaucracy. Most libertarians do not value increasing inequality for its only sake, but tolerate it as a side effect of curtailing state bureaucracy; most socialists do not value increasing state bureaucracy for its own sake, but tolerate it as a side effect of decreasing inequality. This is what I mean when I say parties are not mere inversions: just because they are each united by a broad-bundle of opposing policies, it is not because they are exact mirror images valuing what the other hates and vice-versa. If possible, both parties’ voters would alike probably prefer there to be both minimal state bureaucracy and minimal inequality—they just prioritize their relative importance differently. If, after an election, socialists and libertarians could implement reforms on the condition that they both signed off, they could probably find some way to trade the most bureaucratic enhancement of equality for a less bureaucratic alternative, even if neither party would have implemented this specific reform individually. The resulting (pareto-optimal) compromise would also likely be more appealing to the median citizen than either party’s maximum program, despite having been negotiated by hardliners.

Elaboration: Let us stipulate, to make a maximally difficult situation, that libertarian voters actually both hate state bureaucracy and actively want economic inequality. Similarly, socialists hate inequality and actively want state bureaucracy. (Note: Both of these are obviously untrue in our world.) If we have a Libertarian Party who moderately values inequality and highly opposes state bureaucracy, while we have a Socialist Party which moderately values state bureaucracy and highly values equality, they can both find themselves better off in the end if they trade away state bureaucracy for additional equality, despite them not agreeing on what is “good”. Imagine that previously a Liberal Party had implemented a paternalistic welfare program which directs $1400/year/person in purchasing power to the poorest 10% in society. They heavily regulate what poor people can buy (only organic food, no cable TV, no brand name clothing), and send inspectors out at regular intervals to make sure they are following the rules. This costs $600/year/person in bureaucratic overhead. After the Liberals are swept out of power, there is a hung parliament with the Socialists and the Libertarians as the two largest parties. They come to an agreement: ditch the invasive policing of poor people and give the subsequent savings as an expanded annual welfare payment. This is neither side’s first choice of policy, but both are better off: the Libertarians do not like that poor people are getting more money, but they are willing to fire state bureaucrats and re-rout their previous salaries directly into the hands of less-encumbered consumers (who will spend it in the market anyway); the Socialists do not like firing state bureaucrats, but rerouting the salaries from those in the 60th percentile (as the welfare bureaucrats are in this society) to the poorest in society is worth it to them. Again, this is a ridiculous scenario where the parties are stipulated to have exact opposite views (the Libertarians actively hate poor people and the Socialists actively love state bureaucracy), and they still can both come out better off because they are not symmetrical, valuing different interests above the other.

Game Theory: Why About Five is Different From Two

We do not want to be ruled by a dictator because we have discovered that they always—and must—govern badly. Consider Mao: he wanted to make life for peasants better,7 yet his regime starved tens of millions of them to death. That a dictatorship did this is not hard to explain. When one’s position in society is determined by the whim of just one individual, the optimal “strategy” is to focus on humiliating rivals at the expense of everything else. Thus the top ranks in a dictatorship will always be filled with intensely competitive courtiers, because ever telling an uncomfortable truth, or letting a rival get too entrenched, or focusing attention on long-term policy details, or any other distraction will get oneself smeared, demoted, and punished. The type of person who can survive in an environment like this will also be the type of person who allows bad decisions to become crises to become catastrophes to become world-historic crimes without having the competence or incentive to intervene.

A good system takes amoral ambition and channels it into socially useful activities. It is good to humiliate a rival if the only way to do so is by revealing genuine corruption. It is good to stay in power if the only way to do so is to preside over a growing economy. Representative democracy re-orients the selection of the powerful to such a diffuse audience that policy becomes the dominant lever of influence. If a policy will make many voters angry and no voters happy, it is probably a bad policy. Charles Haughey’s platform was not, after all, “make Charles Haughey very rich.” In those rare cases when “the people” are genuinely mistaken about their own interests, then it becomes imperative for politicians—for their own political benefit—to convince the voters. This constant dialectic between leaders educating voters and voters disciplining leaders is the core of what makes representative democracy so much more effective than oligarchy or dictatorship. Mao’s lackeys would have found a less murderous road to industrialization if they were worrying about how the peasants would vote.

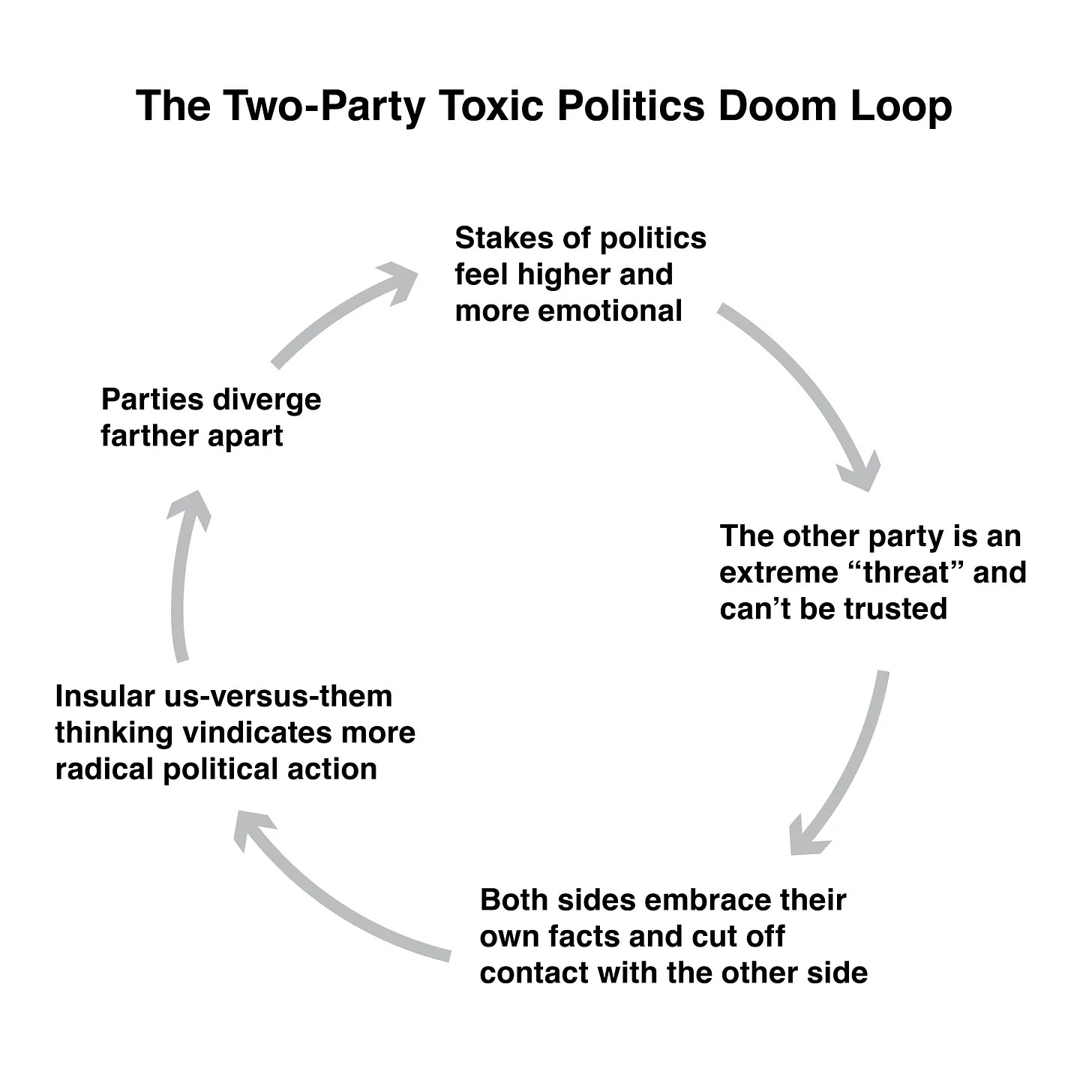

But if democracy is so good, and compromise so possible, why is our system such a disaster? In Lee Drutman’s memorable phrase, we have a “Two-Party Doom Loop”:

The American political system as it emerged out of the 1780s had several contradictory features. Perhaps the most consequential for today is the way that it overlaid two-party election procedures8 with a requirement of concurrent majorities across multiple branches of government. In order to implement policy, one faction needs to control or at least mollify four distinct institutions with different selection methods and time horizons: the Presidency, the House, the Senate, and the judiciary. This has not happened in living memory, except for a brief (and disastrous) period during Bush II (2003 - 2007). Instead, whatever party wishes to rule must get some degree of buy-in from their opponents.9 The field of mathematics and logic which describes the best strategies for competing individuals and institutions is called “game theory”. The game theoretical analysis of this situation is clear: preventing the party in power from doing anything to help people is a sure-fire way to undermine their appeal, and when there are only two parties, it is okay to do something unpopular if it makes the other guy even more unpopular.

Parties do fail to compromise in multi-party systems. Just last fall, the German FDP (pro-business centrists) broke their coalition with the center-left SPD and Greens. They had secretly planned a calculated campaign to weaken their former partners and then win the ensuing snap election. This partially worked: the SPD and Greens lost almost 40% of their support from the previous election. However, the FDP lost over 60% of their support and were wiped out of parliament. What makes this example of failed compromise different than the American equivalent is that all parties involved could be punished. While the FDP ultimately took the most blame, it did not redound to the benefit of their former partners—rather, it was the other opposition parties who grew. If, instead, the FDP-SPD-Green coalition had found ways to work out a mutually agreeable and effective solution to Germany’s problems, then they likely would have lasted in power. They could not and so another coalition now gets to try. In America, by contrast, a failure of negotiations just leads back to… the same two parties negotiating again. This is not an incentive to compromise!

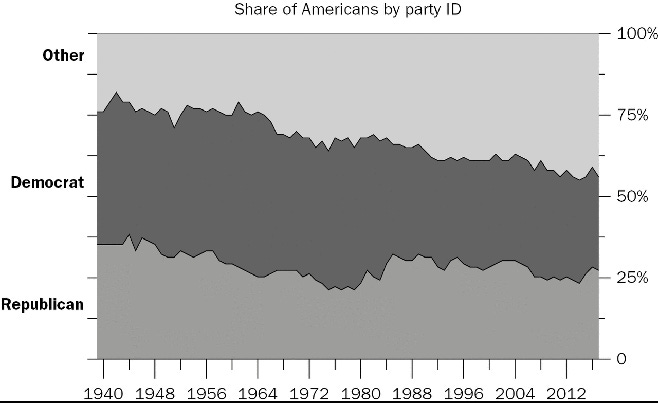

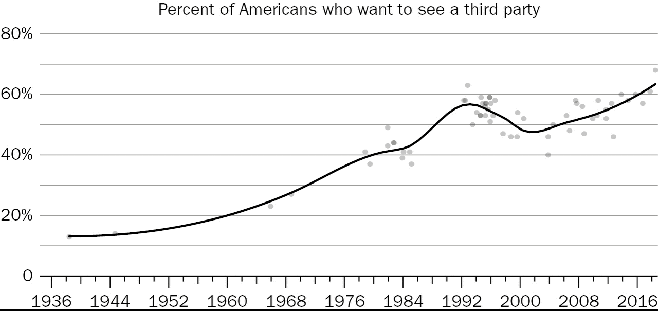

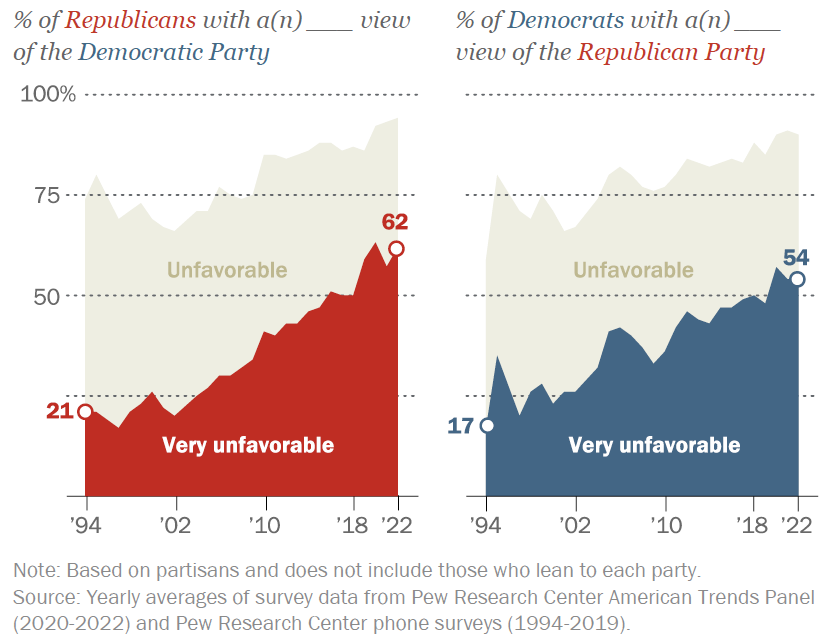

To share another observation from Lee Drutman’s excellent Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop, Americans have expressed increasingly dissatisfaction in their choices even as they have also become more resolutely partisan.

How is this possible? Because even as they come to dislike their own party, they have come to dislike their opponents even more!

Is This Just An Argument For Market Freedom In Politics?

I think my argument is agnostic on whether market freedom is freedom, but its logic does closely align with the less controversial aspects of pro-market ideology. Most agree that, without a strong countervailing reason, lowering regulatory barriers to competition gives the consumers products which are on average both higher quality and more in tune with their tastes. I do not, in this case, see a strong countervailing reason to stop us from lowering the regulatory barriers to allow about five rather than two parties to compete, but that does not mean there is no such reason when it comes to tariffs, labor unions, education, or other sectors where some do see benefits from regulatory barriers.

I think, due to the one-person one-vote nature of this proposal, its underlying logic can just as easily be equated to a sort of market socialism (though one heavily mitigated by the vast inequalities in the society in which these “equal consumers” of parties are embedded). I would expect—on average, over time—people will use their vote to make the economic system better for most people, and it is an empirical question about whether that will drag competing parties towards or away from market forces. I think a strength of multi-party reforms is that anyone who is not actively oligarchic believes that their side will win to the extent that their views objectively benefit people, and I think the decentralized and organic nature of political direction allows a much better exploration of why and how different policies work.

I do not want to imply this election was otherwise above-board. It is bad that tens of thousands of minorities were purged from the voter rolls, that an asymmetrically misleading ballot was introduced, that the recount was blocked by partisan goons, and that the Supreme Court broke all procedure to give the presidency to their preferred candidate. It is also bad that the election was decided using an antiquated and undemocratic system like the electoral college. It’s not obvious to me that a Gore win would have improved the country’s trajectory, but it is definitely not-good that he was defeated the way he was.

The Robert Caro biographies are good on this, and it is especially a focus in The Means of Ascent (1990).

As early as 2019, Matt Bruenig wrote in Politico:

In last night’s debate, Biden showed the country once again that his brain is not fully functioning. He could barely get through a sentence without losing his train of thought or starting over. I kept expecting him to wander off the stage with a thousand-yard stare. I can’t be the only one who sees this. At some point, you have to think that Biden’s Bad Brain will have some kind of effect on his level of voter support.

A crude calculation which assigns 20% of costs to a grocery store to fixed costs and the rest to variable costs indicates that a store which raises prices 30% can lose almost 60% of their customers and still come out more profitable (.02<1.3x-.78x-.20). This number overstates the fraction of grocery revenue devoted to fixed costs while ignoring economies of scale; these assumptions push in opposite directions, making the estimate broadly accurate.

This is admittedly a very American name to give a social liberal party.

While combining multiple measures into one can form a useful glue (neither can axe what they gave the other without losing what they got too), if doing both together is less than 0.5x efficient, the parties would probably just do them as a quid-pro-quo (investment in R&D and decarbonization separately, rather than R&D for green energy).

Some people think dictators are always “secretly evil,” but I do not see how one reconciles the extremely arduous path Mao took to power with anything but genuine interest in the lives of peasants like himself. He was also an egomaniacal freak, but there is no contradiction between those things.

I hear you say “The Founders didn’t implement a system of two-party election procedures. They didn’t even want parties!” I implemented the “get fat routine” by eating cake every night before bed, regardless of my intentions.

Why is this a new problem, then? Lee Drutman has a story I find mostly convincing: prior to about 1990, politics was only nominally national—ticket-splitting and inter-party ideological overlap was common enough that America had a “four party” system. Such a system meant that—say—Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats could both reap the political success of a compromise, forcing other parts of their respective parties to the table if they did not want to be left behind.